On January 5, 2026, the CDC reduced the number of vaccines routinely recommended for all American children from 17 to 11. The vaccines for rotavirus, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, influenza, meningococcal disease, and COVID-19, all standard for decades, now require either a high-risk status or a discussion with a doctor before a child receives them. This is the most substantial change to the childhood vaccine schedule in decades. For parents, it means shots that would have been automatic at child healthcare visits now require a conversation with their pediatrician, or at least an explicit request. The vaccines still exist. Insurance still covers them. But the default has shifted.

Understanding what changed requires understanding what these vaccines actually prevent and why they were recommended in the first place. Some of these diseases are familiar, like the flu, while others, like rotavirus, may be unfamiliar precisely because vaccination made them rare. Each carries different risks, affects different age groups, and has a different history in the United States.

What “No Longer Routinely Recommended” Means

The CDC calls this new category “shared clinical decision-making,” a term that sounds neutral but represents a real change in how pediatric care works. Under the old system, doctors followed the schedule unless a parent raised objections, and the schedule itself carried the weight of a federal recommendation. Under the new system, the doctor is supposed to present the vaccine as an option and wait for the parent to weigh in, which means the conversation starts from a different place. The change does not reflect new safety concerns about any of the six vaccines. The formulations are identical to what children received last year, and no new research drove the decision. What changed is a policy decision about who should receive them by default. Made by officials who have long argued that American children get too many shots too early. The scientific consensus on these vaccines remains what it was before January 5, but the federal recommendation no longer matches it.

The American Academy of Pediatrics announced it would continue recommending all six vaccines under its own guidelines. Many pediatricians have said they will follow the old schedule regardless of what the CDC says. But the CDC’s position carries weight with insurers, state health departments, and parents who trust federal guidance, so the practical effect extends beyond what any individual doctor decides. For parents trying to make their own decisions, that means knowing what each of these 6 vaccines actually does.

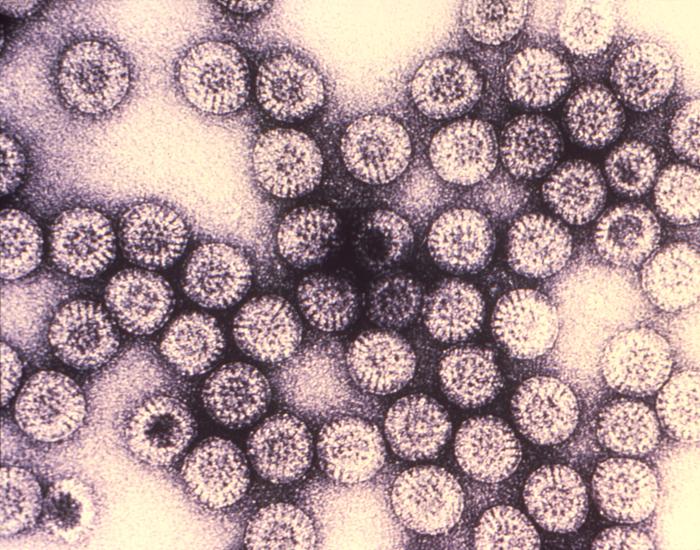

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is a stomach virus that causes severe diarrhea, vomiting, and fever in babies and young children, and the danger is dehydration. Small bodies lose fluids fast, and without treatment, the condition can become life-threatening within days. Before the vaccine became available in 2006, doctors called it “winter vomiting syndrome.” Because it tore through pediatric wards every cold season. Almost every child in the United States encountered the virus at some point. The numbers from that era are hard to forget. About 70,000 young children were hospitalized, and around 50 died from rotavirus each year in the U.S., according to CDC data cited by NPR. Pediatrician Sean O’Leary of the University of Colorado described it as “a miserable disease that we hardly see anymore,” and that rarity is a direct result of vaccination.

The virus has not disappeared. It still lives on the surfaces babies touch, from toys to changing tables, and it spreads easily in childcare settings. Vaccination rates have kept it in check, but infectious disease specialists warn that lower rates will bring back the hospitalizations. The infrastructure that once handled tens of thousands of sick babies each winter no longer operates at that scale. Which means a resurgence would hit hospitals that are no longer prepared for it.

Rotavirus is violent and fast, a disease of the gut that typically resolves within days. The next two vaccines on the list target a different organ entirely, and the consequences of infection can take decades to appear.

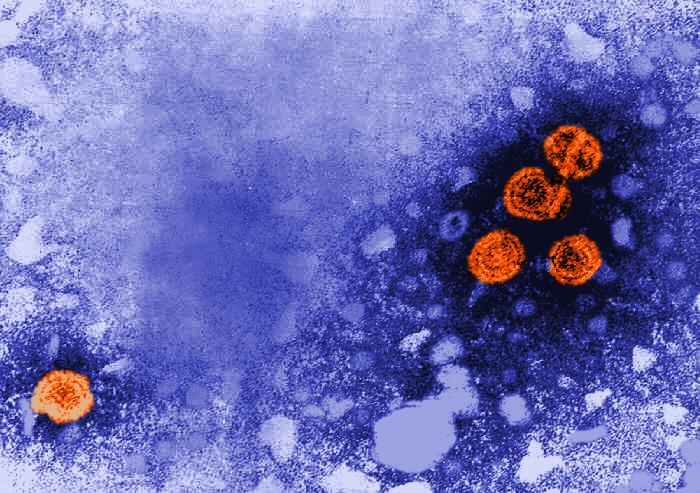

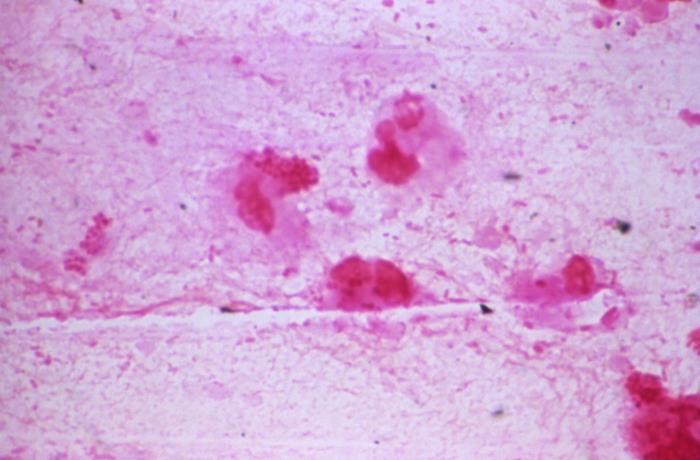

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver. It spreads through blood and bodily fluids, including from mother to baby during birth, and it behaves very differently depending on when a person contracts it. Adults who get hepatitis B usually clear the infection on their own, but babies almost never do. According to data from Johns Hopkins and the CDC, as many as 9 in 10 infants infected in their first year of life will develop chronic, lifelong infection. Up to 25% of those chronically infected will eventually die from liver failure or liver cancer, often decades after the initial infection with no symptoms in between. The damage happens slowly and silently, which is part of what makes the virus so dangerous in young children.

Doctors gave the vaccine at birth for more than 30 years precisely because of this timing issue. Waiting even a few months creates a window of vulnerability, and vaccinating only infants born to mothers known to be infected has already failed as a strategy in the U.S. Doctors still don’t screen about 15% of pregnant people for the virus, according to CDC data. So infected mothers slip through undetected every year. Routine vaccination effectively eliminated chronic hepatitis B in young American children. The virus still circulates, with over 17,000 chronic cases diagnosed in 2023 alone. But those cases are now concentrated in adults who were never vaccinated.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A also infects the liver, but it works differently from hepatitis B. People catch it through contaminated food or water, or through close contact with someone infected, but it doesn’t become a chronic condition. A person gets sick, recovers, and develops immunity.That does not mean the illness is mild. Symptoms include fever, fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and jaundice, and they can last for weeks. While death is rare, the infection can be severe enough to require hospitalization, especially in older children and adults. Young children often show few symptoms but can still spread the virus to others.

Outbreaks still happen in the United States, often traced to contaminated food at restaurants or in produce. The vaccine has been on the childhood schedule since 2006, and cases dropped more than 90% after it was introduced. The disease was never as deadly as hepatitis B. But it caused enough illness and enough outbreaks that routine vaccination made sense from a public health standpoint. The next vaccine on the list targets a far more familiar illness. One that arrives every year and kills children every season.

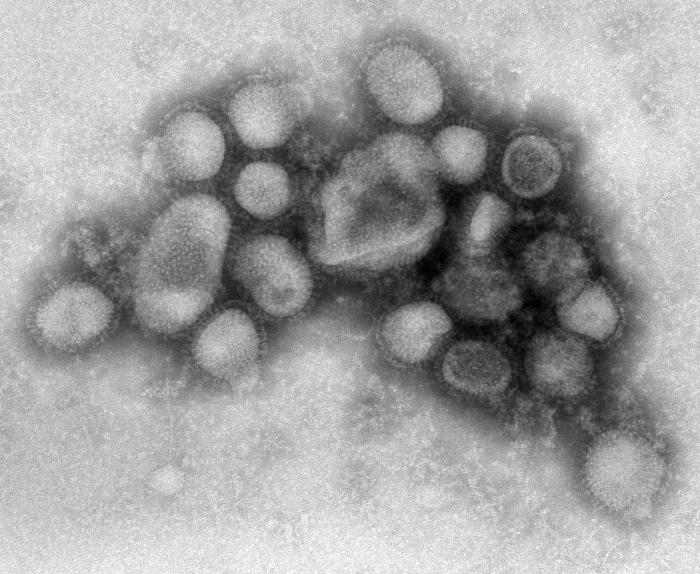

Influenza

The flu needs little introduction. It circulates every fall and winter, and severity ranges from a few miserable days to hospitalization and death. For children, the risks include pneumonia, dehydration, and worsening of underlying conditions like asthma. Healthy children die from the flu every year. In the 2024-2025 flu season, 288 children in the United States died from influenza. The highest toll of any regular season since the CDC began tracking pediatric flu deaths in 2004. 89% of them were unvaccinated. These numbers are not unusual. Pediatric flu deaths occur every season, and the majority consistently occur in children who did not receive the vaccine.

The flu vaccine differs from most other childhood immunizations because it requires an annual shot. The virus mutates constantly, and each year’s vaccine is reformulated to match the strains expected to circulate. This makes it less convenient and, for some, less urgent than vaccines that provide long-lasting protection from a single series. But the annual death toll among children suggests otherwise.

Health officials recommended flu vaccination for all children. Not only because children get sick, but because they spread the virus efficiently to grandparents, immunocompromised family members, and others who face far higher risks from infection. Removing the universal recommendation shifts that calculus to individual families.

Meningococcal Disease

Meningococcal disease is rare, and that rarity is part of what makes it hard to talk about. Most parents will never meet a child who had it. But those who have seen it up close describe something almost unimaginable. A healthy teenager can wake up with flu-like symptoms and be dead by nightfall. The bacteria cause two main conditions. Meningitis is an infection of the lining around the brain and spinal cord, and sepsis is an infection of the blood. Both can progress with terrifying speed, and both can be fatal even with treatment. Johns Hopkins describes meningococcal disease as “rare but catastrophic.” Noting that it can kill a healthy child within hours and leave survivors with amputations or brain damage.

Health officials recommended the vaccine for adolescents, typically at age 11 or 12, with a booster at 16, because teenagers and young adults face the highest risk. The bacteria spread well in crowded conditions, so they urged college freshmen living in dorms to get vaccinated. The rationale for removing the universal recommendation centers on incidence. Cases are uncommon, around 0.13 per 100,000 people in 2023. Though that number has been rising, 2024 saw the most cases reported since 2013. The low rate is partly a result of vaccination, and the argument cuts both ways. The disease is rare, but when it strikes, the consequences are often permanent.

COVID-19

COVID-19 is the most recent vaccine on the list and the most politically charged. Health officials also removed it from universal recommendations first, back in October 2025, before they announced the broader changes to the schedule in January. The virus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, continues to circulate and mutate. Children generally fare better than adults. But severe illness and death do occur, and some children develop long-term symptoms after infection. The vaccine was added to the childhood schedule in late 2022. With the goal of reducing both individual illness and community transmission.

Uptake was never high. By 2023, fewer than 10% of eligible children had received the vaccine, making it an outlier on the schedule. Federal officials cited this low uptake as one reason for removing the universal recommendation, and because healthy children face a lower risk from the virus than other age groups. The vaccine remains available through shared clinical decision-making. Parents who want it for their children can still get it at no cost. What has changed is that the federal government no longer recommends it for every child.

The Rationale and the Response

The administration offered several reasons for the changes. The primary one was to match the schedules of peer nations. A December 2025 presidential memorandum directed the CDC to compare the U.S. schedule with those of other developed countries, and Denmark in particular, which recommends fewer vaccines. Officials argued that the U.S. was an outlier in recommending so many shots and that scaling back would restore public trust. The response from the medical community was swift and largely critical. The changes were made without input from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the expert panel that has traditionally guided vaccine recommendations through a public, evidence-based process. The American Academy of Pediatrics released its own vaccine schedule that differs from the CDC’s. A break that had not happened in decades.

Critics also pointed out that the U.S. is now an outlier in the opposite direction. According to KFF, the nonpartisan health policy research organization, the U.S. now recommends fewer childhood vaccines than most peer nations, including Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Denmark, the cited model, is itself an outlier in recommending so few. The stakes are not theoretical. A 2024 CDC report found that among U.S. children born between 1994 and 2023, routine childhood vaccinations prevented 508 million illnesses, 32 million hospitalizations, and more than 1.1 million deaths. The science behind these vaccines has not changed. What has changed is the federal government’s posture toward them.

Navigating Conflicting Guidance

Parents looking for clear direction will find something more complicated. Federal recommendations now differ from those of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and state-level guidance varies depending on where a family lives.

According to KFF, 24 states no longer use the CDC or HHS as their source for vaccine recommendations. These states instead follow guidance from their own health departments or from external expert groups like the AAP. What a pediatrician recommends in California may differ from what one recommends in Texas, not because the science is different but because the policy sources are. School vaccine requirements add another layer. These are set by states, not the federal government, and they may or may not match the new federal schedule. Some states may loosen their requirements in response to the CDC’s changes, while others maintain or even strengthen their existing rules. Parents will need to check what their own state requires for school entry.

The result is fragmented. A parent might hear one thing from their pediatrician, another from their child’s school, and something else entirely from federal health officials. The AAP continues to recommend all six vaccines, and many pediatricians will likely follow that guidance regardless of what the CDC says. But the mixed messaging creates confusion, and confusion often leads to inaction.

What Parents Need to Know

The practical situation is more straightforward than the policy landscape suggests. All six childhood vaccines remain available, and all six remain covered by insurance at no out-of-pocket cost to families. Federal programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, and the Vaccines for Children program, which together cover more than half of American children, will continue to provide these vaccines. Private insurers have pledged to maintain coverage through at least the end of 2026. KFF confirms that parents wishing to vaccinate their children against diseases that are no longer universally recommended may still do so without paying out of pocket.

If a child is behind on any of these vaccines, catch-up doses are still available and still covered. Parents can ask their doctor what the practice recommends, whether it follows CDC or AAP guidance, and what the state requires for school. The vaccines have not changed. The diseases have not changed. What has changed is that the decision now rests more squarely with parents, which makes that conversation with a pediatrician more important than it has ever been.

Read More: Scientists Uncover How Covid Vaccines Might Trigger Rare Heart Issues

Trending Products

Red Light Therapy for Body, 660nm 8...

M PAIN MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGIES Red ...

Red Light Therapy for Body, Infrare...

Red Light Therapy Infrared Light Th...

Handheld Red Light Therapy with Sta...

Red Light Therapy Lamp 10-in-1 with...

Red Light Therapy for Face and Body...

Red Light Therapy Belt for Body, In...

Red Light Therapy for Shoulder Pain...