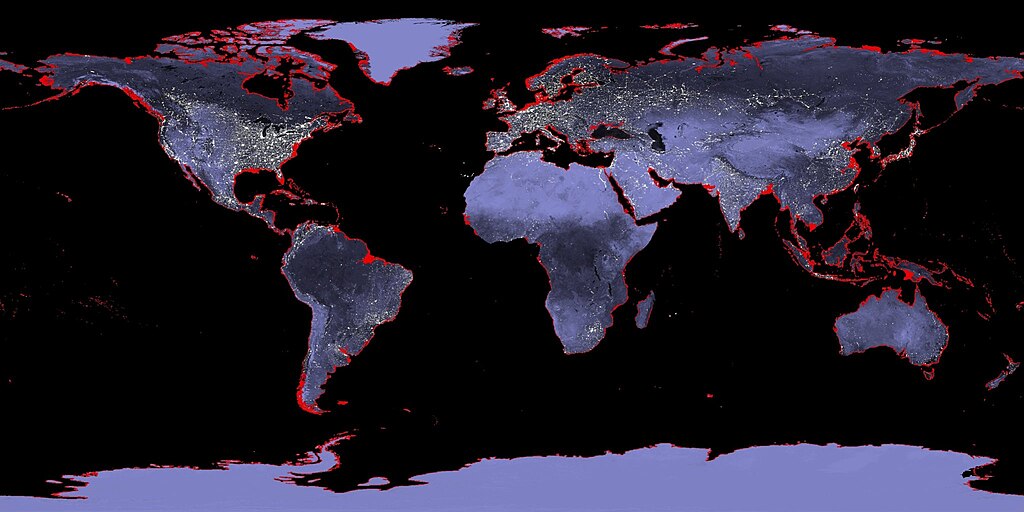

Dozens of major cities around the world face a future underwater. Rising seas and sinking land threaten to push coastlines inland, flooding neighborhoods that millions of people call home. Climate Central, a nonprofit research organization, has mapped these cities at risk using data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 6th Assessment Report, completed in 2023.

The 7th Assessment Report is still in development and won’t arrive until 2029, so this remains the most current global assessment available. Their projections show what could happen if warming continues on its current path. They put many coastal cities at risk of partial or total submersion within the next few years. Some of these places have already started building defenses, but others are running out of time.

Why Some Cities Are Running Out of Time

Many coastal cities sit on ground that is actively sinking beneath them. A phenomenon called land subsidence that happens when excessive groundwater pumping and the weight of urban development compress the earth. When sinking land meets rising water, the problem accelerates far beyond what either force would cause alone. Some cities lose 1 to 10 inches of elevation every year. A city sitting comfortably above sea level today could find itself underwater within a decade.

Bangkok, Thailand

Bangkok sinks more than half an inch every year, and The Guardian has reported that parts of the city could fall below sea level by 2030. The Thai capital sits on soft clay at just 5 feet above the waterline, so there isn’t much room for error. In 2011, floods killed hundreds and left a fifth of Bangkok underwater. Projections suggest Suvarnabhumi International Airport could see regular flooding in the years ahead. The city has responded with infrastructure like Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park, which can hold a million gallons of rainwater during the monsoon season.

Jakarta, Indonesia

North Jakarta sinks 8 to 10 inches per year. One of the fastest rates on Earth, because illegal wells deflate the ground from below while urban sprawl adds weight from above. Close to 90% of the metropolitan region already lies below sea level, according to C40 Cities research. And more than 60% of its 10.6 million residents live in flood-vulnerable areas where the poorest face the greatest danger. The situation is so dire that the Indonesian government is building an entirely new capital called Nusantara on Borneo.

Venice, Italy

In 2019, water submerged 90% of Venice at levels not seen in half a century. The city sinks a fraction of an inch every year. While the high tides that flood its streets grow more frequent. Venice has pinned its hopes on the MOSE flood barrier system, a project first designed in the 1980s that took decades to complete. The barriers can block incoming tides from the Adriatic Sea. But they require constant maintenance, and as sea levels keep rising, even the best engineering may not keep pace.

Miami, United States

Miami’s sea levels rise faster than the global average, and what makes it worse is that traditional defenses won’t work. Because South Florida sits on porous limestone, seawater seeps up through the ground even when walls block it from the sides. Flooding already contaminates drinking water and damages roads across a metro area that sits almost entirely at low elevation. With nowhere higher to retreat. Environmental author Jeff Goodell told Business Insider he sees no scenario in which Miami exists at the end of the century.

New Orleans, United States

New Orleans was entirely above water when it was first developed in the 1800s. But about 5% had dropped below sea level by 1895, 30% by 1935. And today, more than half the city sits beneath the waterline, some parts 15 feet deep and sinking two inches per year. Decades of oil and gas drilling accelerated the process. A 2016 NASA study projected that the entire metropolitan area could become submerged by the end of the century. Levees and flood walls offer protection today, but they were not built for what’s coming.

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Ho Chi Minh City’s eastern districts sit on flat, heavily developed marshland that Climate Central’s maps show turning red by 2030. With Thủ Thiêm and areas stretching into the Mekong Delta facing the greatest danger. The city center may avoid full submersion, but flooding and tropical storms will grow more severe with each passing year, and Vietnam’s largest city has already felt the strain. Repeated flood events have pushed infrastructure to its limits while the costs of repair and recovery keep mounting. Millions of residents now depend on systems that were not designed for the conditions arriving.

Manila, Philippines

Manila sinks about 8 inches per year, 7 times faster than global sea levels are rising, according to the data. Excessive groundwater pumping has pulled the capital below sea level in some areas. While 20 typhoons hit annually, and drainage systems cannot move water fast enough when heavy rains arrive. If current trends continue, Earth.Org projects that nearly the entire population could face displacement by the end of the century, and unlike wealthier cities facing similar threats, Manila has limited resources to adapt.

Shanghai, China

Shanghai’s timeline runs longer than the other cities on this list, but its eventual fate carries consequences for the entire global economy. Parts of the city have dropped more than 10 feet since 1921, according to Earth.Org research. And some areas still sink up to half an inch per year. Shanghai has slowed the damage through groundwater regulations, buying itself time that cities like Jakarta do not have. The trouble is that supply chains and global markets depend on Shanghai’s port, so even gradual flooding will send costs rippling outward long before the city itself goes under.

Amsterdam, Netherlands

Amsterdam’s defenses have held for centuries, but they were built for a world that no longer exists. The city sits low enough that only dams, barriers, and floodgates keep the North Sea at bay, and current infrastructure can handle roughly 3 feet of sea level rise. Projections suggest seas could climb 4 to 6.5 feet by 2100. Which means more than 700,000 people, 97% of the population, could face displacement according to Earth.Org. Dutch engineering may be the only reason Amsterdam belongs in a conversation about long-term survival rather than imminent collapse.

Rotterdam, Netherlands

Rotterdam sits up to 20 feet below sea level, but the city stopped trying to wall out the water. It pioneered infrastructure that works with flooding, turning parking garages into reservoirs and designing plazas to flood during storms and buy time for drainage. Climate Central projections suggest seas could rise 3 to 8 feet by 2100. Which would force the main storm surge barrier to close far more often. Dutch engineers now consult with vulnerable cities worldwide, but whether these innovations can scale fast enough remains an open question.

Georgetown, Guyana

Georgetown has relied on seawalls since colonial times, including one structure stretching 280 miles along the coast, and approximately 90% of Guyana’s population lives in areas that depend on these aging defenses. Climate Central places the city among those most likely to face severe damage by 2030. The walls already need constant reinforcement as storms grow stronger and tides reach higher. Guyana has oil reserves that could fund adaptation, but building new infrastructure takes time, the city may not have.

Khulna, Bangladesh

Khulna, Bangladesh’s third-largest city, sits just 29 feet above sea level, and the country’s 2021 floods showed how vulnerable it remains. Waterborne diseases already pose serious public health challenges that increased flooding would only worsen, and residents have few resources to relocate or rebuild. Bangladesh produces just 0.3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet faces some of the most severe consequences, and international adaptation funding has not arrived at anywhere near the scale needed to close that gap.

Basra, Iraq

Basra sits amid canals, streams, and marshland that make it especially vulnerable to rising seas. The surrounding wetlands, partially restored after being drained under Saddam Hussein’s regime, now face saltwater intrusion. The city already suffers from waterborne illness outbreaks that increased flooding would only worsen, and as a hub for Iraq’s oil industry, flood damage here could disrupt energy supplies well beyond the region. Critical facilities sit in zones that may become regularly inundated within years.

Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria’s beaches have already begun disappearing as Mediterranean waters rise. NPR has reported the sea could climb as much as two feet by 2100. According to a UN Security Council session, the rise will affect 25% of Egypt’s population and 90% of its agricultural land. Ancient landmarks and archaeological sites face destruction. While local authorities have started building barriers to protect farmland from saltwater, these address symptoms rather than causes.

Kolkata, India

Kolkata is sinking as groundwater pumping compacts the soil beneath it, a process called subsidence, and with sea levels rising at the same time. The gap between water and land closes from both directions. The city’s large impoverished population has the fewest options when flooding arrives because informal settlements along riverbanks face the greatest danger, and residents lack the resources to relocate. Kolkata reflects a reality visible across South Asia, where dense populations concentrate in flood-prone areas because affordable housing exists nowhere else.

Lagos, Nigeria

Lagos sits on lagoons and swampland that drain poorly during heavy rains, and growth has outpaced protective infrastructure for decades. Wealthier neighborhoods have seawalls, whereas informal settlements along the waterfront lack protection. At a UN Security Council meeting, representatives warned that hundreds of millions of Africans will face climate-related displacement by 2030, and some low-lying cities will become uninhabitable. Nigeria’s economic capital may be among them.

Malé, Maldives

The Maldives lies barely 3 feet above sea level and has long recognized its precarious situation, a fact known to most nations. Rising tides don’t just threaten infrastructure here. They threaten existence. Malé’s airport and the artificial island of Hulhumalé face serious risk from even modest increases in water height, so the government has begun building a floating city as a potential refuge. The Maldives represents the frontline for small island nations, places where entire populations may need to relocate within a generation.

Banjarmasin, Indonesia

Banjarmasin, the City of Thousand Rivers, sits below sea level on a swampy delta. Climate Central’s maps show the Barito River regularly overflowing its banks by 2030. The flooding threatens residential areas and the indigenous Banjarese culture that has developed here over centuries. Indonesia already struggles with Jakarta’s vulnerability and lacks resources to protect every threatened city, forcing difficult choices about where to invest in defenses and where to plan for managed retreat.

Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo sits on Tokyo Bay. Exposed to both sea level rise and storm surge from typhoons, substantial portions of the metropolitan area could flood without effective countermeasures. At the UN Security Council session on rising seas, Japan’s representative called the threat as imminent as an invasion by a foreign nation. Tokyo has resources that poorer cities lack, but even wealthy nations cannot engineer their way out of every scenario.

Read More: New Study Predicts Grim Future for the Arctic by 2100 if Climate Change Persists

Houston, United States

Parts of Houston sink two inches per year from excessive groundwater pumping, according to the World Economic Forum. Hurricane Harvey made the consequences clear in 2017 when it damaged nearly 135,000 homes and displaced around 30,000 people. The lower the city sits, the worse such flooding becomes, but Texas has continued developing flood-prone areas anyway, adding more people and property to the danger zone.

What These Cities Face Next

For the cities that could disappear by 2030, the timeline for action has nearly run out. Some nations have already started relocating capitals, as Indonesia is doing with Nusantara, while others invest in floating infrastructure and water parks that double as reservoirs. But these defenses cost money that wealthy nations have, and poorer ones do not. By 2050, C40 Cities projects that more than 800 million people in 570 cities could face a serious risk from rising seas. With economic costs from flooding reaching one trillion dollars. Resources for adaptation remain as unequally distributed as the emissions that caused the problem.

Read More: Rising Seas Push Whole Nation Toward Full Evacuation

Trending Products

Red Light Therapy for Body, 660nm 8...

M PAIN MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGIES Red ...

Red Light Therapy for Body, Infrare...

Red Light Therapy Infrared Light Th...

Handheld Red Light Therapy with Sta...

Red Light Therapy Lamp 10-in-1 with...

Red Light Therapy for Face and Body...

Red Light Therapy Belt for Body, In...

Red Light Therapy for Shoulder Pain...